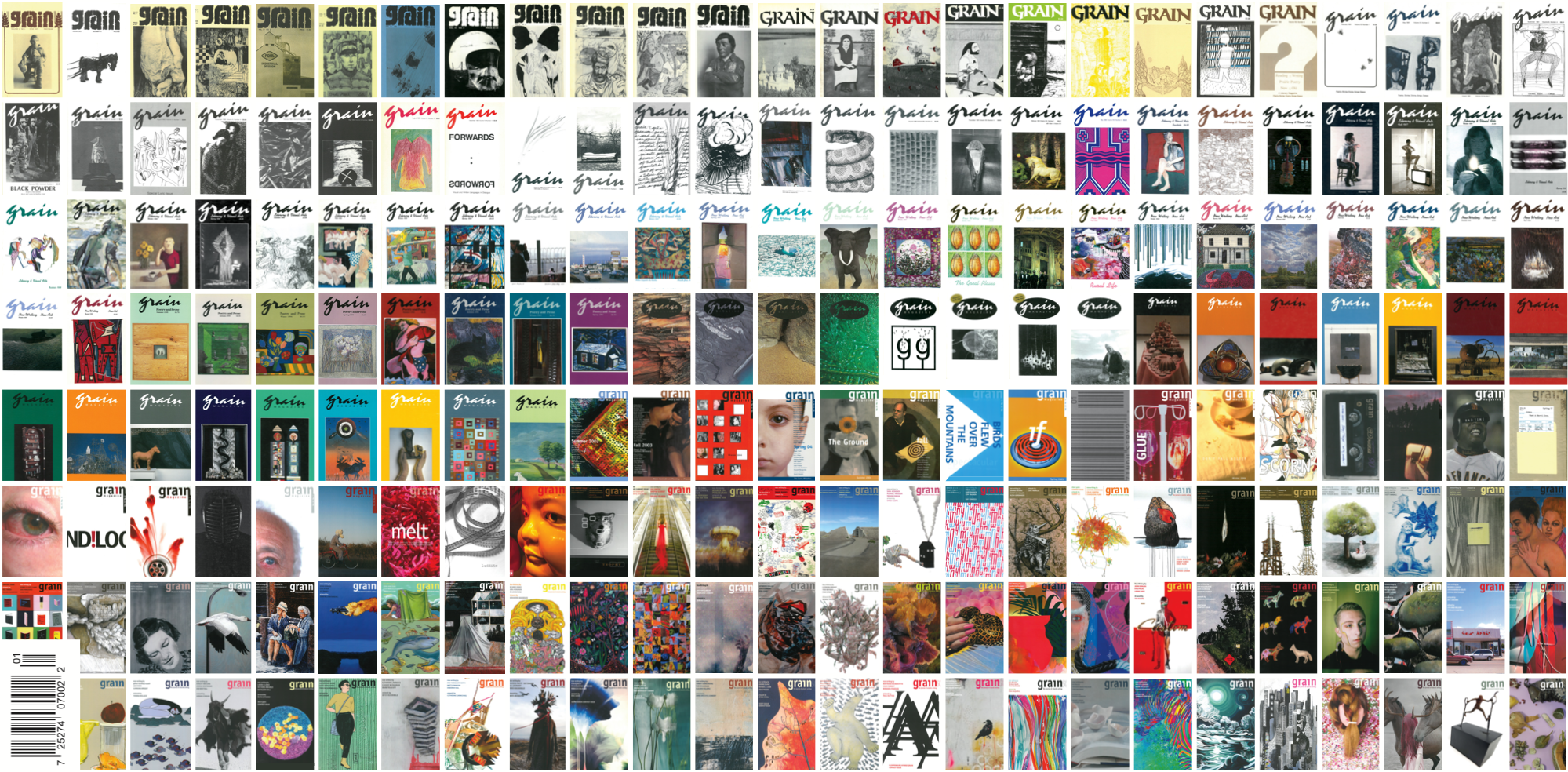

We’re not supposed to judge a book by its cover. But we do. We make assumptions, question the quality of writing, then ultimately decide whether or not to invest into the book our time and money. Book publishers know it, and magazine editors know it, too. But sales and marketing isn’t why, for 199 issues, the cover art for each issue of Grain was thoughtfully selected. And it’s not why fifty-two years worth of covers were crafted into one beautifully designed, fold-out cover, for this, Grain’s 200th issue.

To mark this milestone, I wanted to remind readers of Grain’s long history, of the writing and writers that have been published, and of the influence Grain has had on Canada’s literary community since it was seeded in 1973. As Grain’s 25th editor, I’ve tried to keep my promise to the founders to continue the harvest—to continue to showcase the best of eclectic writing. So I asked myself, how best to get your attention? The answer: don’t tell, show. Let’s have you take a visual trip, via cover, all the way back to that first harvest, Volume 1.1.

In addition to the poems and stories featured in this issue, which includes the winning pieces from the 37th annual Short Grain Contest, judged by Fawn Parker and Conor Kerr, is an essay written by none other than Grain’s first managing editor, Neil Besner, whose own writing journey began right here in Saskatchewan. We’ve also included, what I hope will begin a new tradition, a Blast From the Past—a poem by Mark Abley, originally published in Volume 1.1, which happens to be his first-ever published poem.

This special issue, as every issue does, comes together because of Grain’s phenomenal team, for whom I am very thankful. A mountain of gratitude to associate editors, Taidgh Lynch and Credence McFadzean; art editor/designer, Shirley Fehr; proofreader, Kendall Rude; and SWG staff, Andrea MacLeod, Tea Gerbeza, Tracy Hamon, Debbie Sunchild-Peterson, Cat Abenstein, Yolanda Hansen, and Ashwina Parmar, for all the ways you help and support Grain.

Like the editors and art designers before me, I have aimed to grab your attention, evoke an emotion, and represent, through visual art, the incredible writing published here. So judge this book by its cover. Make assumptions. And if I’ve judged correctly, you’ll agree that the writing in this 200th issue is spectacular.

- Elena Bentley, Editor

RAPTURE [excerpt] | Iryn Tushabe

The day I turned fifteen, I saw my mother walk on fire. It was outside the Church of the Redeemed, the compound hedged with thickets of pencil cacti. The pastor, who called herself a woman of God, laid a short path with burning charcoal: an approximation of hell. When no one from her mob of hallelujah-amens volunteered to go first, she gave it a go and lasted two seconds. One step, two steps, and she jumped off to the side calling to her God in Rukiga, her flowery English momentarily forgotten. Mama lasted six steps longer, possibly because the soles of her feet were tough as the mpingo tree. She reserved her sandals for Sunday services and special occasions, not the mid-week fellowship to which I’d unwillingly accompanied her. She singed her feet good and proper. Charred flesh the colour of tar sizzled and clung to the glowing coals. A nauseating smell saturated the air.

Our government-funded dispensary was perpetually without medicine. Dr. Yuda scrounged, syphoning every last drop from several empty bottles. “If it were up to me,” he said as he injected Mama with what little penicillin he’d drawn, “that crazy pastor would go to Luzira for life.”

“That we should be so lucky!” Baba said. Luzira Maximum Security Prison was in far-away Kampala and housed our country’s death-row inmates.

The doctor also gave Mama Panadol for the pain, said to hang in there and keep the wounds clean. “I’m expecting a new shipment of penicillin.”

Each morning before walking the ten minutes to school, I washed Mama’s wounds with salty water boiled over the kerosene stove.

“Glory to the most high,” she said, smiling when I pressed gently against the hardening scabs.

In those early post-burn days, her life seemed less burdened as though she were living on a different, dreamlike plane. The tombs were gone from her eyes. Perhaps this burning had instilled in her a greater fear of hell, which surely awaited her if she carried on as she’d been doing.There had been days when I came home from school and the dishes from the night before were still piled up in the basin, the floors unswept, my mother, in her nightdress, staring out the window at nothing or lying in bed, pale and damp as though dreaming of being consumed by fire. I brought her a tray with chai and mwana akaaba buns, but she turned to face the wall. Her life and death struggle had been expansive and unyielding. I saw her as a woman who wasn’t sleeping, but gone. When she dismissed me to go prepare supper, I made haste. What I should have done was smooth her damp hair and say I love you. And say, Tell me what it’s like being so sad all the time.

MY BROTHER, ON THE FENCE | GABRIEL SAYERS

I see him still

a pulse—

my brother that night

Indistinguishable

as the cloudburst’s blue-yolk,

crept the edge of the yard

long before the thunder,

as leaf piles spread barren,

a scattering of birds

the scuttering of beetles

the setting of the evening,

I could only watch—

little hands

petrified beneath the sun

couldn’t feel

the warmth of the lighter

he held to his cheek,

couldn’t form the expression—

a flicker, cleaved breaths,

flush along the fence

watching the shadow of my brother

raking leaves behind the shed.

SEVENTY-THREE TRIBUTE CANDLES [excerpt] | DILAN QADIR

We were so thrilled by the opening of N&S Herbal in a mall in Burnaby that none of us foresaw the scandal it would spark. The grand opening, held on March 21, 2024—the first day of the Kurdish New Year—was accompanied by a media blitz. A popular local publication ran a glowing feature, titled “Healing from the Middle East,” asking readers if they’d ever heard of using parsley capsules to treat kidney stones or anise seed to boost milk production in breastfeeding mothers. But what resonated most wasn’t the remedies themselves—it was the pride we felt as Nusyar and Sayran, a Kurdish couple, launched a business that combined cultural heritage with an entrepreneurial spirit. They weren’t just herbalists; they were ambassadors of our traditions, serving clients from all walks of life. For the Kurdish community, it was a moment to celebrate, a reason to hope.

But then it all fell apart—or rather, he fell apart.

Nusyar was quite the character. A nursing school dropout, he’d dabbled in exorcism and experimented with bloodletting before finally settling on herbalism. At the store, he’d set up a small corner shrine—a portrait of his late father flanked by a pillar candle that seemed to burn continuously. The candle scents alternated between sage and rosemary, but it wasn’t the fragrances that raised eyebrows. Not only was candle-burning not a part of our cultural traditions, but such public displays of emotion were rare for Kurdish men, who were often expected to keep their grief private.

Still, this eccentricity was minor compared to what truly piqued our curiosity: Nusyar’s habit of cornering men during weekend prayers at the Kurdish mosque in Burnaby. He’d pull them aside one by one, leaning in close to whisper something in their ears. His head bobbed in affirmation as he spoke, and the exchange always ended with a few hearty pats on the back. Speculation ran wild. Was he offering a business deal? Laying out some kind of plan? Whatever it was, he wasn’t sharing it with the rest of us.

Nusyar was an enigma. His round, bald head caught the fluorescent lights of the mosque’s prayer hall, gleaming above a stoic face framed by glasses perched on a prominent nose. His expression betrayed nothing. Yet his wide, slightly hunched shoulders lent him an aura of wisdom, especially when he clasped his hands behind his back and gave someone his undivided attention.

Whether he realized it or not, Nusyar seemed to command notice, drawing attention in ways that felt both deliberate and accidental. In this regard, his wife, Sayran, was not less striking.

LANGUAGE IS FOR LOVERS | HENAR PERALES

If the night sky is for the frogs

Throbbing at the first sign of dusk

do their tongues not unfurl in the void

waiting for the flesh of prey

and is that not a kind of love

a kind of faith, though you forgot your first love

was your mother’s tongue

oiling your fur

How she sent you clean

into the world saying

remember your tongue is only as good

as your interlocutor

And: remember

my hands before

they folded into fists

warm as caves

She sang standing at the stove

But what’s the difference

between faith and hope

between tongue and praise

She sang remember

what passes for love

is like opening a hand

under water

________________________

Citation note: Title is a line borrowed from Terrance Hayes’s poem, “Shakur.”